Understanding Ritual, Part 1: Religious Rituals

22 November 2020

Jump to summary

“Ritual.” We shy away from the word, perhaps associating it with apostate formalism, pagan polytheism, or even cultic demonism. If someone asked you, “Do Latter-day Saints engage in rituals?” you’d probably say no.

But we do engage in rituals. The sacrament is a ritual. Baptism is a ritual. Fasting is a ritual. Nearly all our acts of worship involve ritual. So what is ritual? Why do we use it, how does it work, and how can we better employ its unique power? In this post, I hope to answer these questions and then apply that knowledge to better understanding our most common ritual: prayer.

(Acknowledgements: In this post, I draw heavily from the theory of ritual developed by sociology and anthropology, as taught to me in winter 2020 by Dr. Kerry Muhlestein, an Egyptologist and a professor of ancient scripture at BYU.)

What Is Ritual?

A ritual is an established pattern of actions, gestures, and words that, taken as a whole, conveys a larger symbolic, ceremonial, or religious purpose beyond mere utility.

Our world is steeped in ritual. It pervades nearly every religion. Animal sacrifice in ancient Israel (and in many other religions), the Jewish Passover, and Christian baptism are all rituals. Marriages and burials the world over are surrounded by rituals. Making the sign of the cross is a ritual. Ritual even pervades non-religious spheres: flag ceremonies, inauguration into public office, and school commencements all include ritual elements.

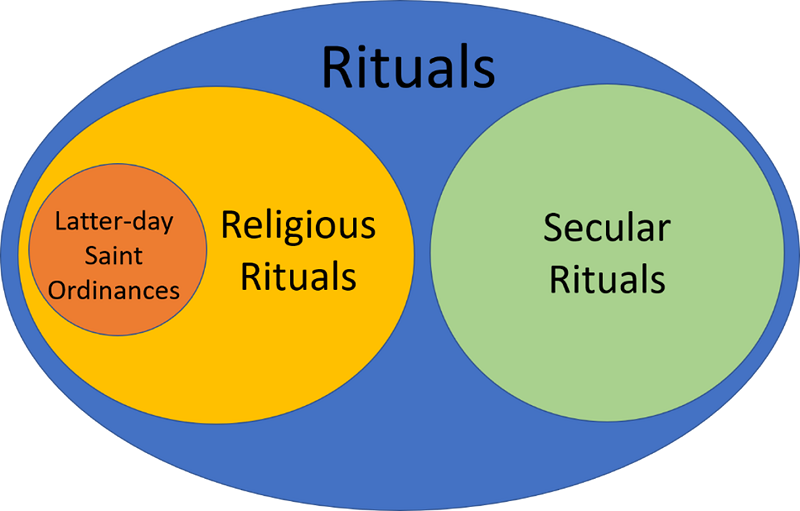

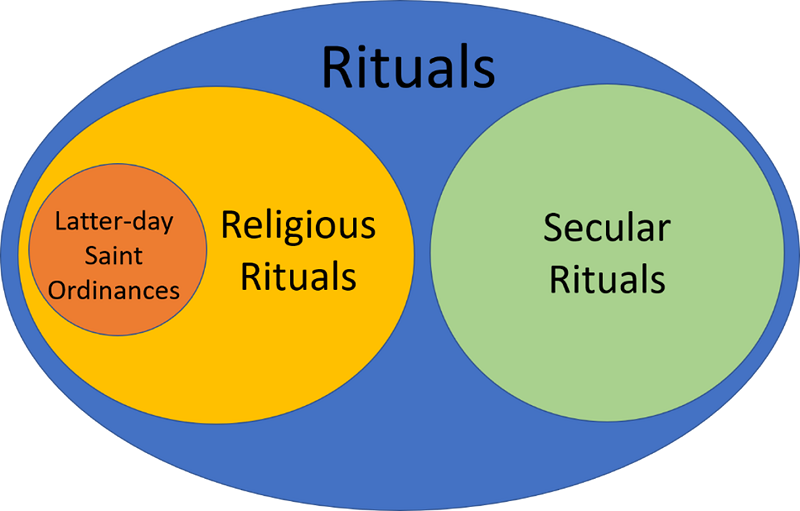

Perhaps one reason we avoid the term “ritual” as Latter-day Saints is because most of our ceremonies we call “ordinances.” While there is a lot of overlap between these two words, ordinances are best categorized as a smaller category within rituals: ordinances must be performed by priesthood bearers, while rituals don’t have to be. The Venn diagram below clarifies these relationships.

Today I will focus on religious rituals, saving secular rituals for another post.

The Purpose (and Power) of Ritual

The purpose of religious ritual is to do something that cannot be done by mundane (non-ritual) means.

Rituals tap into powers normally inaccessible. Rituals affect the sacred or spiritual plane, rather than the temporal plane. Through rituals, we can control or influence things beyond our normal power to control.

An example is the ritual of fasting. By engaging in a prescribed set of actions (beginning with a prayer, going for two meals without eating or drinking, then ending with a prayer), we tap into heavenly power in a way we never could through everyday means, or even through prayer alone. Fasting “unlocks” certain blessings and heavenly interventions that are otherwise unavailable (Isaiah 58:9; Matthew 17:21).

[Pro tip: If you hover over a scripture reference or footnote, you can see the associated text.]

Now, some may say, “The power of fasting isn’t in its ritual aspects, but in the exercise of faith.” But this is creating a false dichotomy: the power of fasting is in having the faith to undertake the ritual.

True, it is possible to fast, or to do any other ritual, without the faith and the proper intent. Jesus rebuked such insincere fasting (Matthew 6:16), and so did Isaiah (Isaiah 58:3–5). But in both cases, their answer was not to do away with the ritual entirely and focus on “faith alone”: their answer was to let inner faith and commitment fuel the outer performance (Matthew 6:17–18; Isaiah 58:6–7). Thus if we perform any ritual “not with real intent of heart . . . it profiteth [us] nothing” and is “not counted unto [us] for righteousness” (Moroni 7:6–9).

Elements of Ritual

Rituals vary greatly over time and cultures, but nearly always they involve sacred actions performed by a sacred agent in a sacred space in a way that invokes sacred time. (“Sacred” means “consecrated” or “set apart,” or different from the mundane or everyday.)

- Sacred actions can include words, music, vestments, objects, gestures, or performances, and often carry symbolic or doctrinal meaning. Common sacred actions throughout religious history—both inside and outside the Judeo-Christian tradition—have included ritual meals, offering of animals or foodstuffs at an altar, washing with water, burning of incense, annointing with oil, set prayers or chants, processions, hymns, and ritual dramas.

- Sacred agents: often, the ritual must be performed by a sacred or set apart agent, such as a priest, or administered by the priest to other participants (such as in baptism). The sacred agent often symbolically represents a divine or heavenly figure. For example, in the sacrament, the priests and deacons represent Christ.

- Sacred space is usually a location built and consecrated specifically for sacred use, such as a chapel, shrine, or temple. These sacred spaces typically represent or stand in for something else. For example, the baptismal font is in “similitude of the grave” (D&C 128:13), and various rooms in the temple represent different heavenly spheres.

- Sacred time refers not to the time of day, but rather to a time of great cosmic significance. The ritual in effect transports the participants to that time. For example, the sacrament takes us to the time of Jesus’s suffering in Gethsemane and Calvary.

Most rituals involve two, three, or all four of the above elements.

Application: Prayer as a Ritual

Let’s see how we can use ritual theory to enrich our understanding of the most common ritual in our lives: prayer.

Chart: Prayer as a Ritual

|

Purpose

|

To transport our thoughts from this mundane plane to a sacred plane as we commune with God.

|

|

Sacred actions

|

Reverent posture: kneeling (where possible), with eyes closed, hands folded or clasped, and head bowed.1 2 We are also encouraged to vocalize our prayers, when possible (D&C 19:28).

Formulaic words: “Our Father in Heaven” (opening); “In the name of Jesus Christ, amen” (closing)

|

|

Sacred agent

|

None; in this, the most universal of our rituals, all are welcome to participate, even the most sinful or wayward.3

|

|

Sacred space

|

While we can and should pray anywhere (Alma 32:10; 34:20–27), the Savior taught that we should find a private, reverent, and quiet place to pray (Matthew 6:5–6).

We are also commanded to pray in chapels (Moroni 6:5, 9; D&C 59:9) and temples (D&C 88:119; Isaiah 56:7), and heartfelt prayers in such sacred spaces can be especially efficacious (see 1 Kings 8:29–50).

|

|

Sacred time

|

The ritual of prayer symbolically transports us to God’s heavenly temple, to the moment we kneel before His throne (Hebrews 4:16; 10:19–22; Revelation 8:3–4).4 This is why we kneel, bow our heads, and speak with reverence: because all these actions invoke the image of a servant or child humbly approaching their King.

|

Knowing all this about prayer, how sacred it becomes! How special of a privilege! How powerful of an action! To be able—in any moment, at any place—to spiritually and symbolically rise above this fallen world, kneel in the presence of our Creator, and express to Him our thoughts and feelings!

So What?

Do our prayers manifest the sacredness and holiness that they ought? Knowing that prayer brings us ritually before the throne of God, does it seem proper to say our evening prayers lying in or half-kneeling on our beds? Or to say a hurried, half-distracted prayer before a meal? Or to repeat the same trite phrases and empty expressions over and over again?

My challenge to you: For the next 24 hours, make every personal prayer a sacred ritual by doing these three things:

- Make an extra effort to find a sacred space and a sacred posture. Kneel where possible. Find a place where you can be alone.

- Pause before you begin. Clear your mind of distractions, and visualize yourself before the throne of God.

- Say your prayer out loud.

Try this experiment: 24 hours, starting now. Find the power in prayer. Find the power in sacred ritual, fueled by faith.

Summary

Rituals—established patterns of actions, gestures, and words—are an essential part of our religious experience. The purpose of all religious rituals is to control or influence things on a spiritual or sacred plane, things that would otherwise be beyond our reach. To have power, rituals must be fueled by faith.

Rituals vary greatly over time and cultures, but nearly always they involve sacred actions performed by a sacred agent in a sacred space in a way that invokes sacred time. As we are more deliberate and informed in our performance of ritual, we can tap into greater power in our acts of worship.

Points to Ponder

- How can ritual inform us about group or communal prayer? How can we better participate in group prayer, whether or not we’re the voice?

- How can ritual theory inform your understanding of baptism? Of the sacrament? Of temple ordinances? With each, what sacred actions, agents, places, and times are involved?

Further Reading

- Francesca Gino and Michael I. Norton, “Why Rituals Work: There are real benefits to rituals, religious or otherwise,” Scientific American, May 14, 2013.

- Natalia G., “Praying Out Loud,” New Era, April 2013.

- Russell Ballard, “Watch Ye Therefore, and Pray Always,” Ensign, November 2020, 77–79.

Back to top

Notes

Comments

Besides those I mentioned in my post, what are some more examples of rituals in our lives, religious or secular?

Back to top